How safe are .NET serialization libraries against StackOverflowException

I have always been fascinated by .NET’s

StackOverflowException.

It’s interesting because it’s fundamentally different from most other exceptions—you can’t catch it with

a try/catch block. When you overflow the stack, it’s game over—the runtime will terminate your process.

This behavior is especially devastating for web services that are deserializing user-controlled data. If

your data structure allows recursion, malicious users can easily craft a highly nested payload and use it

to DDoS your website.

Serialization libraries have the power to protect you against this type of DDoS attack by limiting the

recursion depth during deserialization. That’s exactly what libraries designed with security in mind have

always been doing. But they are outliers—most libraries were initially vulnerable to StackOverflowException

(and some of them still are). In this post, I’ll review the most widely used .NET serialization libraries

and show you how they fare against this mighty enemy. You’ll learn which library versions are safe to use,

which serializers require special usage patterns, and which libraries you should simply avoid.

Safe by design

System.Text.Json and Google.Protobuf are the absolute winners. They have

never been vulnerable to StackOverflowException, because they have always been enforcing the recursion limit by default.

This limit is configurable, though, so nothing can prevent you from intentionally increasing it. But nothing can prevent

you from trying to live with grizzly bears, either—it’s just a question of your lifestyle choices.

Previously vulnerable, now safe by default

Newtonsoft.Json is by far the most popular .NET library, with over 2.8B total downloads on NuGet.

Despite its enormous popularity, it was only last year that its insecure defaults were fixed

(see GHSA-5crp-9r3c-p9vr for more details). The vulnerability was

not as bad as it could have been, because you always had the option to control the recursion depth by setting the

MaxDepth property in JsonSerializerSettings (though I doubt many people were doing that). ASP.NET Core users were

not even at risk—

Newtonsoft.Json formatter

has always been safe by default. Long story short, you were vulnerable only if you were doing something like this:

T value = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject(s);

If you’ve been keeping your libraries up to date, even this is no longer an issue.

FlatSharp (FlatBuffers implementation)

and protobuf-net (Protocol Buffers implementation) were also

unsafe by default. Unlike Newtonsoft.Json, these two libraries were 100% vulnerable: there was no option

for users to explicitly set the recursion limit. Yours truly discovered these issues and reported them to both

library authors. James Courtney and Marc Gravell

quickly responded to my reports and immediately published the fixes that made these two libraries safe by default.

Huge thanks to James and Marc for keeping the .NET ecosystem safe!

Unsafe by default, but can be configured for safe use

System.Xml.XmlSerializer from the .NET standard library can be used safely, but figuring out how to do that resembles finding a needle in a haystack. If you are learning how to use the library by following the official documentation, you will almost certainly write something like this:

var serializer = new XmlSerializer(typeof(T));

T value = (T)serializer.Deserialize(stream);

Congratulations, you are now vulnerable to StackOverflowException! Let’s say you decide to up your game by using

some fancy code quality rules.

CA5369: Use XmlReader for Deserialize

comes to rescue with the instructions how to securely deserialize XML:

Deserializing untrusted XML input with XmlSerializer.Deserialize instantiated without an XmlReader object can potentially lead to denial of service, information disclosure, and server-side request forgery attacks.

Denial of service is exactly the thing you want to avoid, so you decide to follow this guideline and wrap

your input stream in an XmlReader:

using var reader = XmlReader.Create(stream);

var serializer = new XmlSerializer(typeof(T));

T value = (T)serializer.Deserialize(reader);

Sadly, this does not protect you against StackOverflowException at all. At this point, you (justifiably) think

it might be wise to revisit your career choices and start raising chickens on a farm. Before you commit to that,

you do one final internet search and magically stumble upon the article

Security Considerations for Data. It takes 35 minutes to read, doesn’t have any useful code

samples, and it’s not even about XmlSerializer. But you are crazy and you read it anyway. By doing so you

become a member of an elite group of people who know how to limit the recursion depth when deserializing XML:

var quotas = new XmlDictionaryReaderQuotas { MaxDepth = 32 };

using var reader = XmlDictionaryReader.CreateTextReader(stream, quotas);

var serializer = new XmlSerializer(typeof(T));

T value = (T)serializer.Deserialize(reader);

If you are somehow doing this, congratulations—you are not vulnerable to StackOverflowException! Not only are

you safe, but I will also buy you a beer (or a drink of your choice) if we ever meet.

Of course, ASP.NET Core got everything right one more time, because this is exactly how the

XmlSerializerInputFormatter works behind the scenes.

So what’s the final verdict for XmlSerializer? If you are using ASP.NET Core to automatically deserialize HTTP

requests in XML format, you are safe. Otherwise, you are most likely unsafe and should consider switching

to XmlDictionaryReader.CreateTextReader.

MessagePack for C# is the most popular .NET library for working with the MessagePack binary serialization format. It used to be vulnerable to denial of service, but then it got fixed and the vulnerability details were published in GHSA-7q36-4xx7-xcxf (fun fact: I reported the vulnerability to Microsoft Security Response Center while it was still unknown, but I got the response that they are aware of the issue, so no CVE for me this time). Unfortunately, even the fixed version is not safe by default—you have to turn on the secure mode explicitly:

var options = MessagePackSerializerOptions.Standard

.WithSecurity(MessagePackSecurity.UntrustedData);

T value = MessagePackSerializer.Deserialize<T>(data, options);

The decision of library authors to introduce secure mode and then keep it disabled puzzles me, because all other libraries have chosen the safe-by-default approach to fix this type of vulnerability. It’s not that easy to figure out that this configuration option even exists: it’s in the security section, buried in the middle of a massive README file. But if you care about security, it’s good knowing that at least you have the option of being safe.

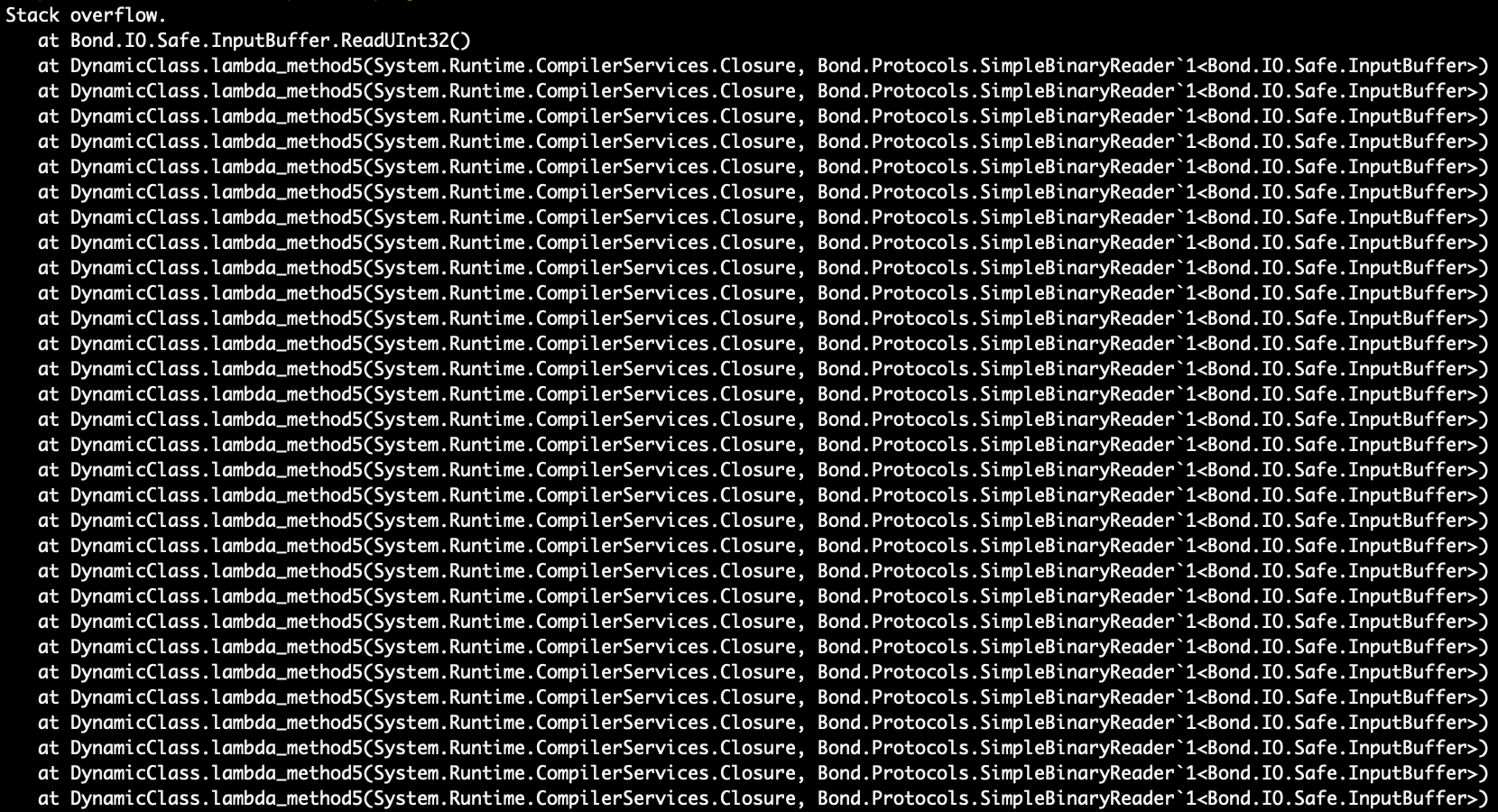

Completely unsafe

Ah, Bond. The only serialization library where the recursion limit doesn’t even exist as an option. That wouldn’t be too terrible on its own, because many other libraries had faced the same issue, but ultimately fixed it. The real problem here is that when I reported this to Microsoft Security Response Center, they just didn’t care. Verdict: avoid.

Update (Mar 22, 2023): I might have been too harsh when I said that MSRC didn’t care about my report. Here is the full story: I reported the issue as denial of service in Microsoft Orleans using Bond deserializer. The report was evaluated in the context of Orleans, and since Orleans is not intended to be publicly accessible (as described in the official documentation), MSRC determined that Orleans users are not exposed to denial of service by design.

Summary

If you don’t like reading and you just want me to tell you how to be safe, here’s a pretty table for you.

| Library | Format | Safe version | Max depth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond | Bond | none | no limit |

| FlatSharp | FlatBuffers | 6.3.0 | 1000 |

| Google.Protobuf | Protocol Buffers | all | 100 |

| MessagePack for C# | MessagePack | 2.1.90 1 | 500 |

| Newtonsoft.Json | JSON | 13.0.2 | 64 |

| protobuf-net | Protocol Buffers | 3.10 | 512 |

| System.Text.Json | JSON | all | 64 |

| System.Xml.XmlSerializer | XML | all 2 | 32 |

Conclusion

If you keep your libraries up to date or use ASP.NET Core formatters, you are most likely safe from

StackOverflowException. Otherwise, you should probably try adopting the guidelines from this post.

But how bad would it be to be vulnerable anyway? Stay tuned for the next post, where the real fun

begins: I’ll show you how denial of service attack looks like in practice.

Huge thanks to Milica Miljkov for editing this post, and also for making it more about users and less about me.