My bug finding chronicles (and how to earn money through vulnerability research)

At least one person has asked me about my thought process when searching for denial-of-service vulnerabilities: how do I choose the target libraries, what specifically I look for in them, etc. “At least one person” meaning “exactly one person”, and that one person happens to be my wife, but I decided to write a whole post on this topic anyway! In this half-memoir, half-tutorial post, I’ll show you the most interesting bugs I’ve found so far and the methods I used to find them. I wouldn’t say I have any advanced bug finding skills, but I do know a few useful techniques, so I hope you will learn something new today.

Finding a panic in the Go standard library

If memory serves me right, my bug finding adventures started in July 2017. Fuzzing was a big thing back then, and I got attracted to it after reading the famous blog post Pulling JPEGs out of thin air. I was learning the Go programming language at the time and after I found this great article on go-fuzz, I finally decided to give fuzzing a try.

The easiest way to get started is by fuzzing some library you are already familiar with. You can’t fuzz just any library, though: in general, the library you want to fuzz should ideally parse or deserialize the input parameters in some way. Or even simpler: if you can’t pass a random byte array (or something convertible to byte array, such as string) to the library, you can’t easily fuzz it.

With these criteria in mind, I then selected two candidates: UniDoc and goftp. There was nothing special about them other than the fact I was using them at that time. You can read the detailed description of these fuzzing adventures in my post Going down the rabbit hole with go-fuzz.

Fuzzing goftp turned out to be the most important milestone in my fuzzing career. I got lucky and discovered a panic (that’s just a fancy word Go people use to call a process crash) not in goftp itself, but in the Go standard library! Here is a seemingly innocent line of code that used to be able to kill your process:

time.Parse("_2 Jan 06 15:04 MST", "4 --- 00 00:00 GMT")

I filed the bug, and it was marked as a release blocker. If seems funny after all these years, but that made me really proud for some reason. In retrospect, had I reported this bug to Google security team, I could have easily earned a bug bounty reward and a CVE. But a more important thing came out of this: I was now hooked on fuzzing!

Finding a panic in the Roughtime library

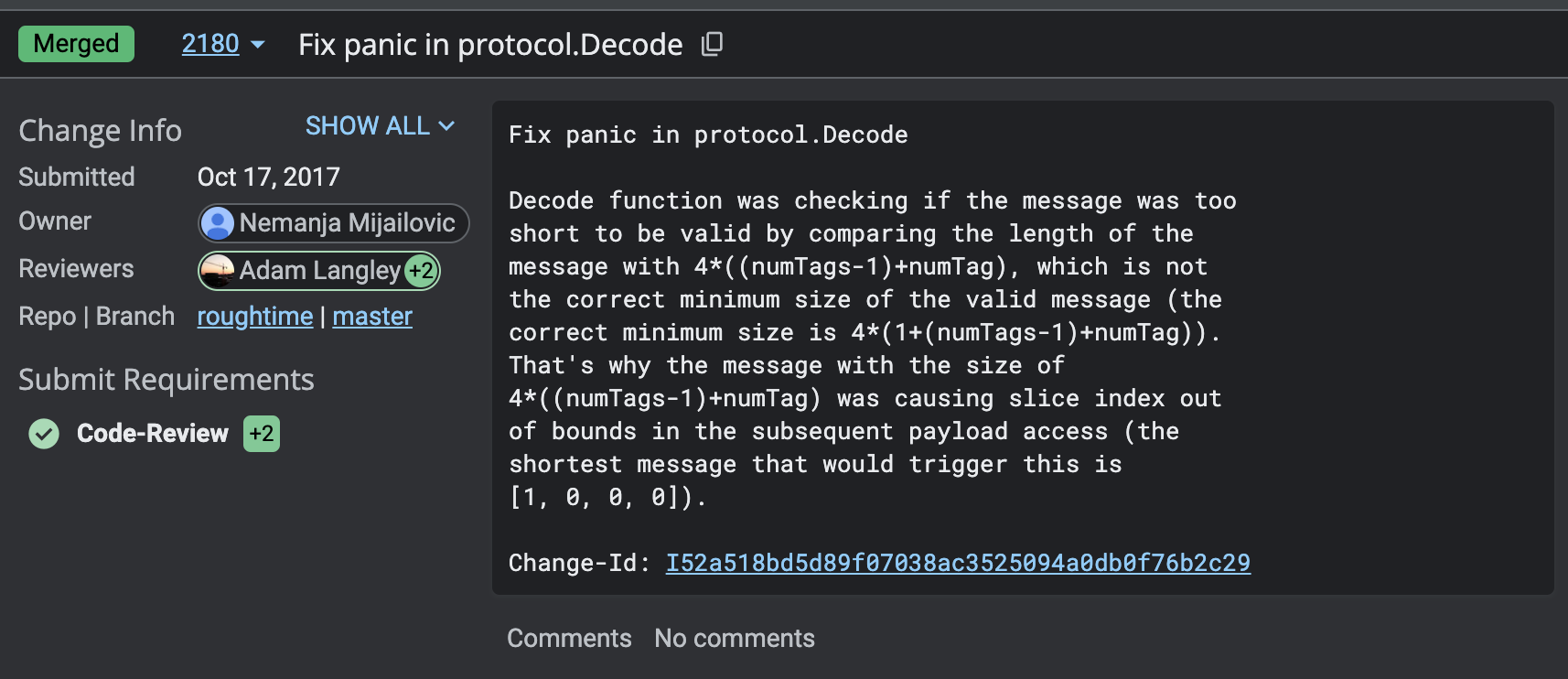

A few years back, I was really into cryptography (proper cryptography, not the blockchain-scam-cryptocurrency type of crypto). I was solving The Cryptopals Crypto Challenges, implementing Noise Protocol Framework and AES-GCM-SIV, that kind of stuff. Somewhere around October 2017, I discovered Roughtime, a secure time synchronization protocol. Why was I interested in it? I have no idea, but it probably just looked cool (everything related to cryptography seemed fascinating back then). I wanted to implement this in C#, so I started reading the code, and somehow I immediately discovered a panic caused by out-of-bounds access (I wish I could recall my thought process from back then). I was extremely proud of this, because the Roughtime protocol implementation was written by none other than Adam Langley, one of the biggest cryptography experts in the world. Again, it seems silly from today’s perspective, but at that time, it meant the world to me. This time, I decided not only to report the bug, but to also become a Roughtime contributor, so I submitted the fix, and Adam Langley himself approved it. I was still not experienced at reporting bugs, so this one didn’t result in a CVE, either. I got this PR approval instead, and it was more than enough for me:

Fuzzing .NET libraries with SharpFuzz

In 2018, I wrote SharpFuzz, and it turned out to be one of the projects I’m most proud of. Five years later, it’s still the only coverage-guided fuzzing tool for .NET. You can read about the SharpFuzz and the motivation behind it in my previous posts. In this section, I’ll focus more on how to choose which libraries to fuzz and how to write the fuzzing code for them.

General fuzzing advice still applies: simply fuzz a library you are already familiar with. Fuzzing works best with deserialization libraries, because parsing code is often highly complex and susceptible to bugs. Another important reason for fuzzing deserialization libraries is that you really can’t afford to have bugs in them. They are likely the first components you call to process user-provided inputs (for example, by parsing an HTTP request with JSON body), which means deserialization bugs can potentially have a catastrophic impact on your service: How StackOverflowException can bring down an expensive compute cluster.

With this in mind, you can choose from dozens of candidate formats: JSON, XML, Protocol Buffers, MessagePack, HTML, YAML, Markdown, CSV, GraphQL, etc. Another interesting category of fuzzing targets contains the libraries that work with file formats: images, fonts, ZIP archives, PDF documents, etc. If you run out of targets, you can also find a few more candidates by looking at NuGet tags such as “serialization” or “parsing” (sorted by popularity if you want to find bugs with the biggest impact), or just Googling for “.NET serialization libraries”.

After choosing the victim library, you need to write the fuzzing function. That’s often

very easy, since most parsers/deserializers load their inputs from a string or a stream (and

SharpFuzz supports both). Fuzzing Newtonsoft.Json?

Fuzzer.OutOfProcess.Run(s =>

{

JsonConvert.DeserializeObject(s);

});

Fuzzing protobuf-net?

Fuzzer.OutOfProcess.Run(stream =>

{

Serializer.Deserialize<Person>(stream);

});

Almost all popular libraries have some basic usage examples in their documentation, and typically you can use them directly in your fuzzing function (it worked for me in 99% of the cases).

If you are still not motivated enough, here is one more attempt to convince you to try fuzzing: if the library has not been fuzzed before, you are very likely to find some bug in it, even if it’s just an undocumented exception.

Finding bugs in the .NET Core standard library

.NET Core standard library is extremely well written and covered with tons of tests. To successfully fuzz it, I needed to write more creative fuzzers and use some advanced tricks. For example, a bug in the library doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll get an unhandled exception or a process crash: a function may seemingly complete without errors, but it could still produce an incorrect result. Fuzzing can help you even in this scenario. Consider this fuzzing function:

Fuzzer.LibFuzzer.Run(span =>

{

string s1 = Encoding.UTF8.GetString(span);

if (!double.TryParse(s1, out var d1) || double.IsNaN(d1))

{

return;

}

var s2 = d1.ToString("G17");

var d2 = double.Parse(s2);

if (d1 != d2)

{

throw new Exception();

}

});

G17 format specifier is used to roundtrip floating-point numbers. That means if you serialize a value using this format, it guarantees that deserialization will return the original value. And how can fuzzing find bugs in the round-tripping code? Simply compare the original number with the deserialized one and throw an exception if they are different. Since fuzzer is instrumenting both serialization and deserialization code paths, it will likely find a mismatch if there is one. Say hello to this .NET Core bug:

var s = "23723333333333333433333337";

double d1 = Double.Parse(s);

double d2 = Double.Parse(d1.ToString("G17"));

Console.WriteLine(d1 == d2);

By design, this code snippet is supposed to print true. SharpFuzz discovered that

on .NET Core 2.2, the result was actually false.

This is just a single example of a more general fuzzing technique. For example, you can compare for equivalence two completely different libraries implementing the same functionality: call both implementations, compare the results, throw an exception if they are different, and fuzzer will try to find the inputs that can trigger this scenario.

Finding CVEs

After using SharpFuzz to find process crashes and hangs in multiple libraries, I realized

that it would be way more fun to figure out how to use these bugs to kill a remote service

(without sending malicious requests to a real service, of course). I picked IPAddress.TryParse

and Uri.TryCreate methods as my first potential targets. My reasoning was that if you are

running a web service, it seems very likely that you will be parsing IP addresses or URLs in

some way (either directly or indirectly by using the ASP.NET Core framework). Whether it was

just sheer luck or brilliant selection of targets, I quickly found bugs in both of these functions.

Fun fact: at this time, SharpFuzz still lacked the support fuzzing .NET Core standard library

assemblies, so I just copy-pasted the source code of IPAddress and Uri classes and created

my own assembly, because I was too eager to find interesting bugs.

What I discovered was that parsing some malformed IP addresses could terminate a process with

AccessViolationException (that’s one of the few exceptions that can’t be caught). Finding the bug

was only the first step towards a potential attack—the next step was to figure out how

to crash the remote service that was calling this function. Conceptually, this is very simple.

In practice, it’s quite time-consuming. You need to look for all usages of the function (in

this case, in ASP.NET Core source code), and determine which ones can receive user-controlled

inputs (for example, headers or body of the incoming HTTP request). One of my favorite tools

for this purpose is .NET Source Browser. It allows you not only to

see the source code of all .NET classes, but to see all of their usages as well. After examining

hundreds of call chains ending in IPAddress.TryParse, I found this one (it later turned out to

be a winner):

ForwardedHeadersMiddleware.Invoke

-> ForwardedHeadersMiddleware.ApplyForwarders

-> IPEndPoint.TryParse

-> IPAddress.TryParse

I didn’t immediately understand the purpose of this middleware. After reading

the documentation, I learned that it’s used when you host your service behind

a reverse proxy. The forwarded headers middleware reads the headers such as

X-Forwarded-For

and sets the associated fields in HttpContext. You could use it like this:

app.UseForwardedHeaders(new ForwardedHeadersOptions

{

ForwardedHeaders = ForwardedHeaders.All

});

Knowing this, crashing a remote service that is using this middleware becomes super

easy. All you need to do is open the TCP connection to the server and send the HTTP

request with the malicious X-Forwarded-For value:

var client = new TcpClient(host, 80);

var stream = client.GetStream();

var request = $"GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: {host}\r\nX-Forwarded-For: {ip}\r\n\r\n";

var bytes = Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(request);

stream.Write(bytes, 0, bytes.Length);

If you are wondering why I didn’t use the regular HttpClient, it’s because it

restricts the values you can put in headers (these evil IP addresses had some

unusual characters in them). I also wanted to emphasize that you don’t need to

be limited by the programming language or the framework you are currently using.

Sometimes, the only thing you really need is the ability to send some bytes over

the network.

Of course, if you decide to start looking for vulnerabilities, please don’t test them against production servers: confirm your findings locally, then report them to service/library owners. If you find a denial-of-service bug in .NET Core, you can even receive a bug bounty reward going up to $5,000!

StackOverflowException

Using SharpFuzz, I also discovered many StackOverflowException bugs (quick reminder that

StackOverflowException terminates the process, so it’s a very effective denial-of-service

attack vector). After some time, I realized that I didn’t really need SharpFuzz for this

purpose—I could easily discover nested recursion bugs manually. You can find the results

of that effort in one of my previous posts:

How safe are .NET serialization libraries against StackOverflowException.

Now, I want to show you my process for finding such bugs. My stack overflow research originally started with JSON format. With JSON, it’s easy to generate deeply nested data: you can concatenate thousands of square/curly brackets in a loop and you are done. With binary formats, it’s slightly more complicated (at least that’s what I thought at first). My initial approach was to serialize nested data structures of different depths and then check the difference between the outputs. This allowed me to generate files that exceeded the recursion limits by simply copy-pasting the diff multiple times. That approach worked reliably until I tried it on FlatBuffers. FlatBuffers is a weird format where there are lot of internal pointers and offsets, so everything breaks if you modify anything by hand. I didn’t really want to learn the format internals, so I had to figure out a better way to generate deeply nested data.

When creating a thread in C#, you can specify its stack size. If you create a thread with

a large stack (hundreds of megabytes), you can use that thread to serialize highly recursive

data without triggering StackOverflowException. Once you have the serialized output, you

can try to crash the deserializer with it. It’s easy, generic, and doesn’t require any

knowledge about the format internals. Here’s the code:

private static T GenerateMaliciousData<T>(Func<T> generator)

{

T data = default;

var thread = new Thread(() => data = generator(), 100000000); // 100 MB stack

thread.Start();

thread.Join();

return data;

}

What’s funny is that I had known this fact about C# threads for 15 years, but it hadn’t occurred to me to use it for this purpose until I hit the roadblock with FlatBuffers.

Conclusion

I hope that you enjoyed my collection of tips and tricks for finding denial-of-service vulnerabilities. They are not the most glamorous type of security bugs, but I love finding them, so that’s more than enough for me. You don’t really need to do what everyone else is doing anyway, so find what you enjoy and do it, whether it’s cryptography, reverse-engineering, finding remote code execution vulnerabilities, or gardening. Have fun and report vulnerabilities responsibly!