Reverse engineering yet another ebook format

In the distant past I was super into removing DRM from books and magazines (check out my posts on that topic: Removing Edge Magazine DRM, Removing Zinio DRM). This interest eventually faded away, mostly because I just stopped using websites that wouldn’t allow me to download and own the products I paid for (kudos to eBooks.com for doing the right thing).

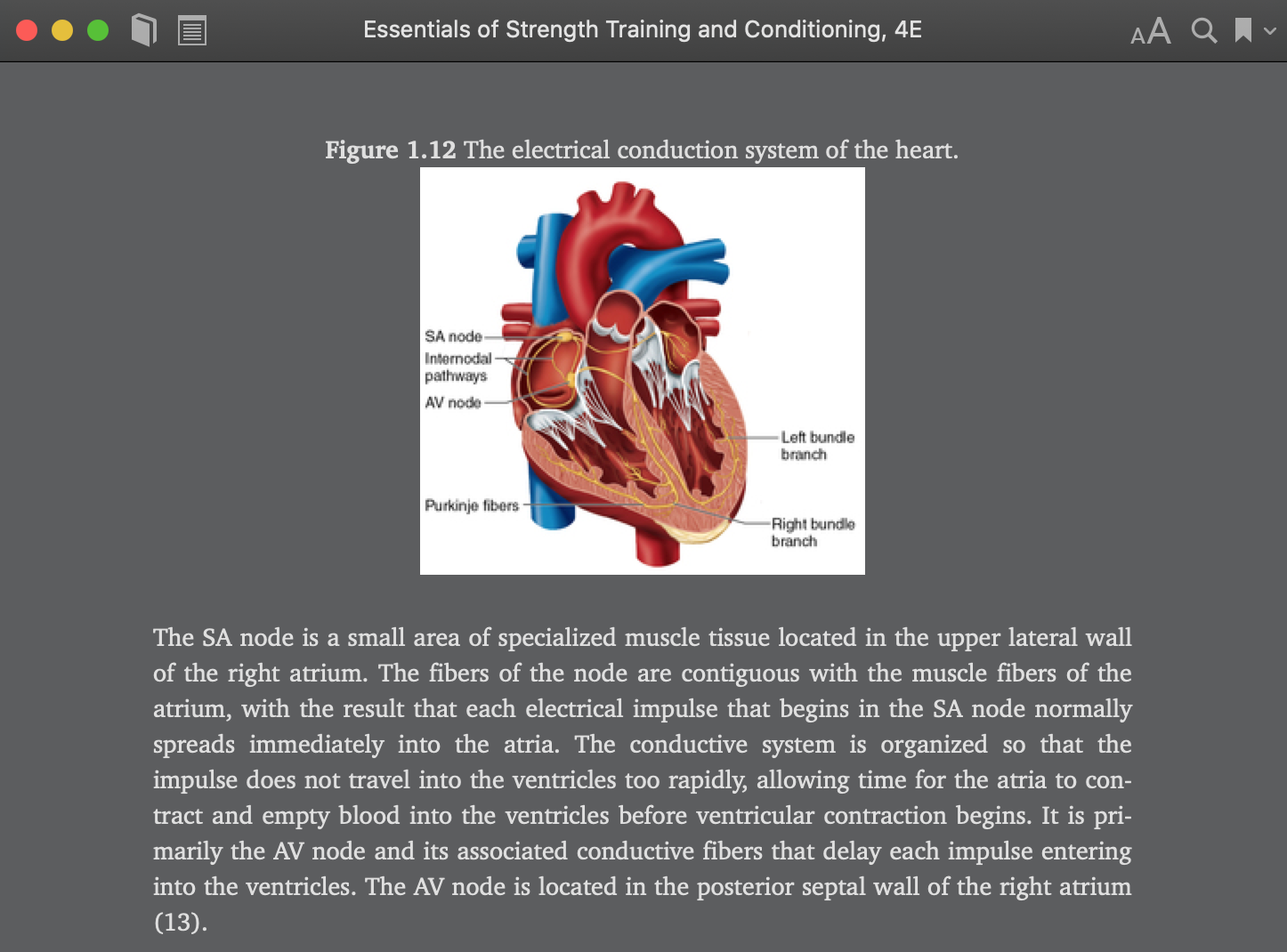

Few weeks ago I decided to buy this book from Human Kinetics. Holding and reading a massive hardcover book before bedtime is not really my cup of tea, which is why I opted to buy it in digital form. The website wasn’t mentioning the format of their ebooks anywhere, so that instantly sounded the alarm in my head. On top of that, the book description said “Access Duration: 84 Months”, and that didn’t sound promising, either (7 years is generous, but anything less than forever is not generous enough in my book). Despite all the warning signs, I went ahead and bought the ebook. And as I had previously suspected, the download option was nowhere to be found. All I got was this:

Gah, not the custom web viewer! Old me would have started reversing the website’s API immediately, but the new me didn’t want to waste any time on that, so I chose to simply ask for a refund. That turned out to be surprisingly difficult—it took me more than 10 minutes to find the refund instructions. I happily clicked the big “Check if your Ebook is eligible for a refund” button, entered my order code and then this happened:

Please enter a valid Ebook code.

The Ebook must have been purchased from a Human Kinetics online store.

Are you kidding me? Had this been a cheaper book, I would have just given up. But $82 is a lot of money in the book world! My old instincts kicked in and I decided it would be more fun to hack and blog for a week than to waste any time dealing with the customer support.

Maybe just print the book?

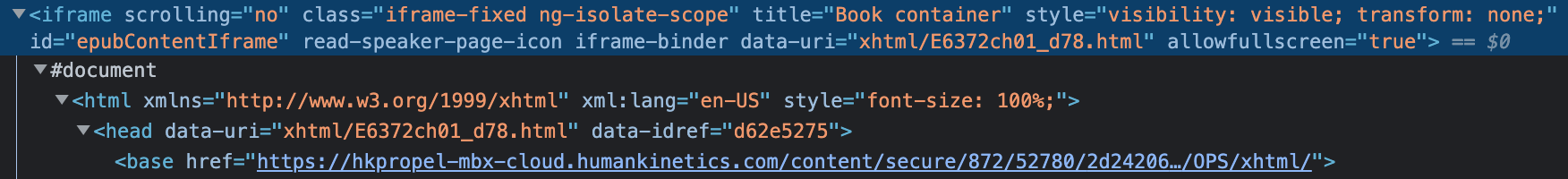

You know you are getting old when your first idea is “can’t I just print the book as PDF and move on with my life?”. Printing the webpage directly wouldn’t have worked, though, because all viewer controls would have been printed, too. But based on the looks of the page, I was pretty sure that part of it was an iframe that contained the actual content of the book. So I inspected the main HTML element in developer tools and found this:

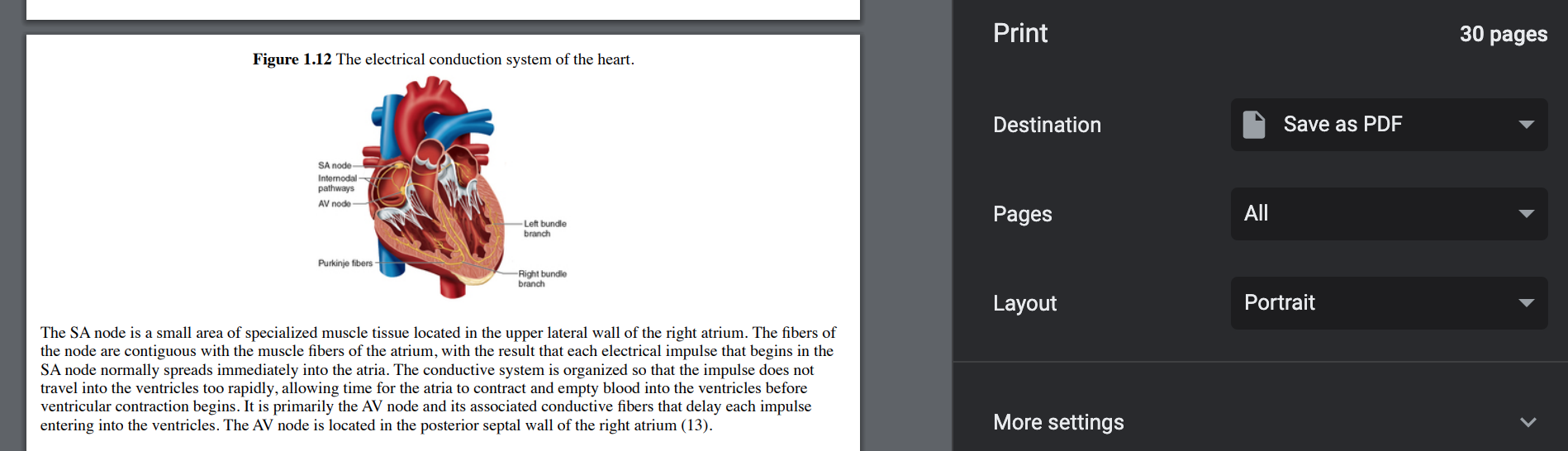

There it was, the iframe with the raw HTML content of the book (more precisely, the current chapter)! I tried to print it and the results were pretty decent:

Finishing the job would have been simple: save all chapters of the book as PDF, then maybe even merge all of them into a single document. But part of me would have been ashamed of half-assing it like that (although I did create a mental note that the solution was good enough for all practical purposes, just in case I fail to find anything better). I was still curious to see if there was a way to retrieve the book in the original format, whatever that format was, so I continued my investigation.

Inspecting the network traffic

I had already figured out how to retrieve the HTML content of a single chapter.

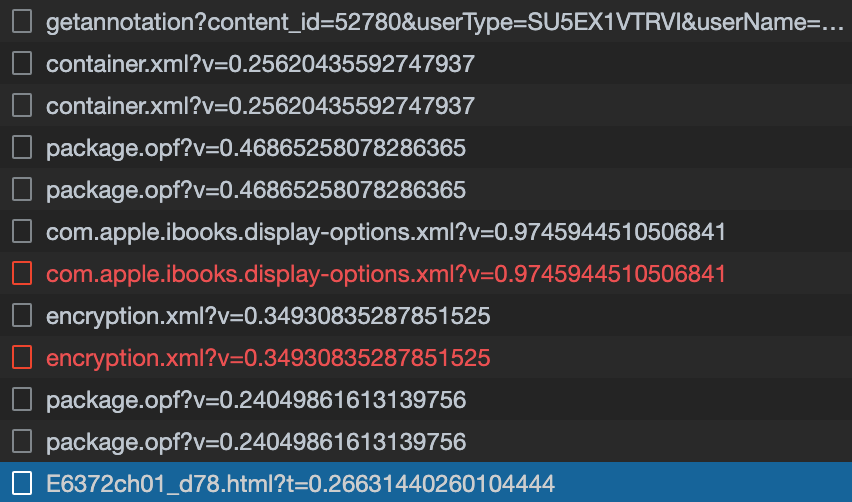

My next idea was to check how the viewer was getting URLs of all chapters, hoping

that I would uncover some API that I could use to get the book metadata. I knew

that the file name of the first chapter was E6372ch01_d78.html, so I looked at

all network requests that came before fetching the chapter itself:

I examined all of these requests, and two of them stood out. Here

is the entire container.xml file:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<container xmlns="urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:container"

version="1.0">

<rootfiles>

<rootfile full-path="OPS/package.opf"

media-type="application/oebps-package+xml"/>

</rootfiles>

</container>

And here are some interesting parts of package.opf:

<item properties="nav" id="nav" href="nav.xhtml"

media-type="application/xhtml+xml"/>

<item id="ncx" href="toc.ncx"

media-type="application/x-dtbncx+xml"/>

<item id="d62e5275" href="xhtml/E6372ch01_d78.html"

media-type="application/xhtml+xml"/>

<item id="d62e5292" href="xhtml/E6372ch02_d79.html"

media-type="application/xhtml+xml"/>

<item id="d62e5310" href="xhtml/E6372ch03_d80.html"

media-type="application/xhtml+xml"/>

This started to resemble some ebook format, but I couldn’t recognize which (probably because I don’t know anything about ebook formats). But now I had two useful clues:

- Book metadata was packaged in

.opffile format. - Media type of that package was

oebps-package+xml.

The next thing I did was search the web for “opf file format”. One of the top results was OPF (file format) page on Wikipedia, which redirected me to EPUB Open Packaging Format 2.0.1. Surprise, surprise, our website was using one of the most popular ebook formats! In retrospect, I could have expected this, but that’s easy to say after the fact. Anyway, now that I knew the format of my ebook, it was just a matter of figuring out how to combine all of its parts into a valid EPUB file.

Recreating the EPUB file

For a few minutes I was worried that I would have to gain a deep understanding of the EPUB format, but everything turned out to be way easier than I expected. Here is an example EPUB file structure from Wikipedia:

--ZIP Container--

mimetype

META-INF/

container.xml

OEBPS/

package.opf

chapter1.xhtml

ch1-pic.png

css/

style.css

myfont.otf

You can read the detailed format description on Wikipedia (I didn’t), but EPUB container is essentially just a ZIP file with three metadata files and a bunch of HTML pages:

mimetypeis always the string application/epub+zip.container.xmlcontains the reference to the.opffile.package.opfcontains the book metadata.- Everything else is the content of the book: HTML pages and their images, CSS styles, fonts, etc.

As we have seen previously, I already had all the metadata files. The remaining steps

were to manually download all the resources, create the required file hierarchy and

compress it into ZIP archive. Downloading the files was super easy, barely an inconvenience—it

was just a matter of finding all href elements in the metadata. I wrote the code quickly, but

I almost had a mini heart attack when the downloads started failing with authentication errors

(package.opf was publicly accessible, but everything else was protected). Fortunately,

the problem was easily solved by taking the HKPropel website cookie from the browser

and sticking it into HTTP client’s headers. And that was it! Did it work? Sure it did:

I don’t know if anyone else will ever need this tool, but it’s available on GitHub: HKPropel downloader. I haven’t written the usage instructions yet, though. If you want them, send me an email or open a GitHub issue, and I’ll be more than happy to write a nice README file for you.

Final thoughts

Unfortunately? That’s not the word I would use if I were selling EPUB books while denying my customers the right to actually own them! I understand that Human Kinetics is probably trying to prevent piracy, since their textbooks are really expensive, but I don’t think that making lives of paying users more difficult is a good way to accomplish that. After all, if someone doesn’t want to buy the book, they can easily download it from Library Genesis (even in superior PDF format, but don’t ask me how I know that).

Ebook publishers, please treat your customers fairly and allow them to download the books they gave you the money for. More importantly, allow me to retire from having to write the tools that bypass your restrictions.